Light Reading (1978) by Lis Rhodes

Thursday, June 6, 2024, 7:30 pm

The Visible Press: Jean-Luc Godard / Lis Rhodes

Presented in association with The Lab

Admission: $13 advance / $15 door / discounted for Cinematheque Members

Event tickets here

1) We must make political films.

2) We must make films politically.

3) 1 and 2 are antagonistic to each other and belong to two opposing conceptions of the world.

4) 1 belongs to the idealistic and metaphysical conception of the world.

5) 2 belongs to the Marxist and dialectical conception of the world.

6) Marxism struggles against idealism and the dialectical against the metaphysical.

7) This struggle is the struggle between the old and the new, between new ideas and old ones.

— Jean-Luc Godard: What Is to Be Done? (The Afterimage Reader)

she was seen and she saw

she was seen as object

she saw as subject

but what she saw as subject

was modified

by how she stood as object

she objected

— Lis Rhodes: Light Reading (1978)

The Visible Press is a London-based independent imprint for books on cinema and writings by filmmakers, dedicated to producing high quality and lasting publications of writings that might not otherwise be available. Managed by film curators Mark Webber and María Palacios Cruz, Visible Press publications include volumes by filmmaker/ideologues Thom Andersen, Peter Gidal, Gregory J. Markopoulos and Lis Rhodes as well as the recent Afterimage Reader. Tonight’s screening celebrates two recent publications by The Visible Press: The Afterimage Reader and Lis Rhodes: Telling Invents Told.

The Afterimage Reader. May 2022; edited by Mark Webber: The independent British film journal Afterimage published thirteen issues 1970–1987. International in scope, it surveyed the many forms of radical cinema during an extraordinary period of film history. Having emerged in the wake of post-1968 cultural and political change, Afterimage charted contemporary developments with special issues on themes such as the avant-garde, Latin American cinema and visionary animation, and also looked back at early film pioneers. It published many of the leading critics of the period and vitally provided a forum for filmmakers’ writings and manifestos.

Lis Rhodes: Telling Invents Told. June 2019; edited by María Palacios Cruz: Since the 1970s, Lis Rhodes has been making radical and experimental work that challenges hegemonic narratives and the power structures of language. Her writing addresses urgent political issues—from the refugee crisis to workers’ rights, police brutality, racial discrimination and homelessness—as well as film history and theory, from a feminist perspective. An important figure at the London Film-Makers’ Co-operative, Rhodes was also a founding member of Circles, the first British distributor of film, video and performance by women artists. Telling Invents Told is the first collection of writings by Rhodes. It includes the influential essay Whose History? alongside texts from works such as Light Reading, Pictures on Pink Paper and A Cold Draft, together with new and previously unpublished materials.

In celebration of these two publications, this mash-up program features works by two artists embodying the political and formalist poles of radical filmmaking, placing Jean-Luc Godard’s aggressively polemical, haranguing and rarely seen Marxist screed British Sounds (1969, co-directed with Jean-Henri Roger) in dialog with a selection of works by British filmmaker Lis Rhodes, including the early-1970s direct film works—Dresden Dynamo (1971) and Notes from Light Music (1975, a single-strip translation of the legendary double-screen Light Music, 1975)—and the cryptic and poetic essay film Light Reading (1978).

SCREENING:

British Sounds (1969) by Jean-Luc Godard & Jean-Henri Roger; 16mm screened as digital video, 52 minutes

Dresden Dynamo (1971) by Lis Rhodes; 5 minutes

Notes from Light Music (1975) by Lis Rhodes; 12 minutes

Light Reading (1978) by Lis Rhodes; 20 minutes

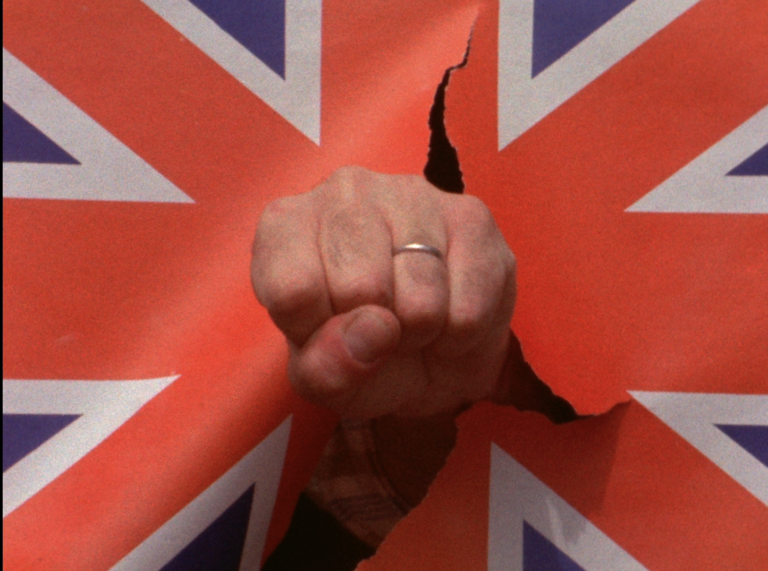

British Sounds (1969) by Jean-Luc Godard & Jean-Henri Roger

Godard’s Maoist-inspired manifesto Que faire? (What is to be Done?), with its injunction to “make films politically,” was written especially for Afterimage 1 (1970) soon after production of British Sounds, which was made under the sign of the Dziga Vertov Group. […]In British Sounds [also known as See You at Mao], typical intertitle texts feature alongside multiple soundtracks, manifesto readings, students rewriting Beatles songs, factory workers, a blood red hand, and an extraordinarily long opening take along an ear-shattering car production line. (Simon Field)

The film was made for (and then banned from) London Weekend Television. It is a documentary in style and form, but designed as a political artifact in which Godard contrives to assault the filmgoer’s sensibility with a series of images and provocations. Slogans flashed on the screen are sometimes humorous, sometimes merely decorative, though Godard would deny this bourgeois reading. Several extended scenes, such as those where Dagenham car factory workers discuss workplace relations, are crisp, simple and also an invaluable record of industrial rhetoric. (Jonathan Dawson: Senses of Cinema)

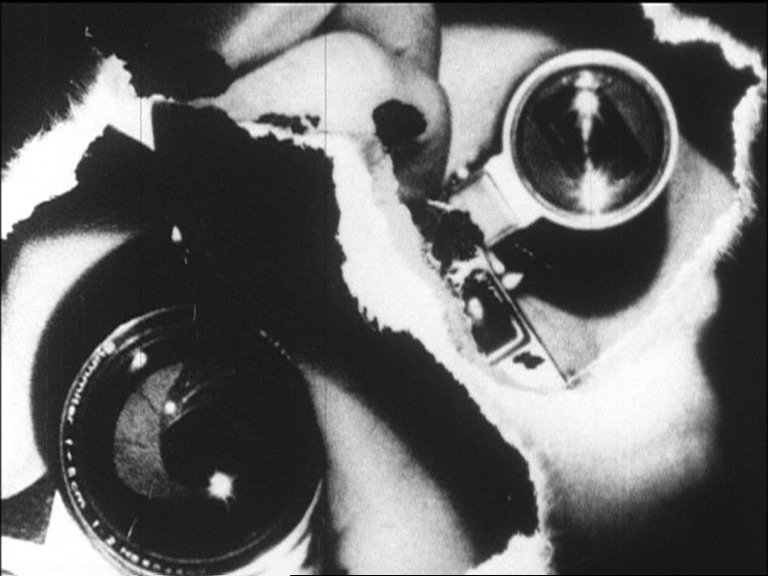

Dresden Dynamo (1971) by Lis Rhodes

It was perhaps the question of sound—the uncertainty of any synchronicity between what was seen and what was said that began an investigation into the relationship of sound to image. Dresden Dynamo is a film that I made without a camera—in which the image is the sound track—the sound track the image. A film document. (Lis Rhodes)

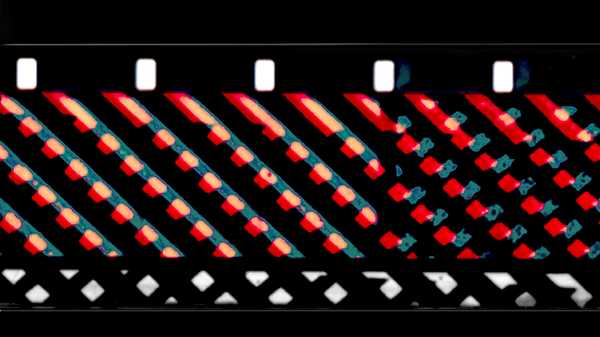

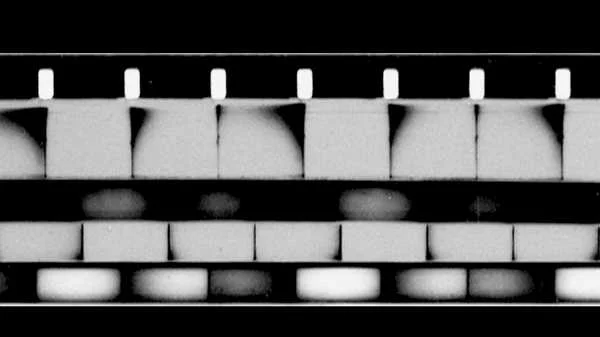

Notes from Light Music (1975) by Lis Rhodes

Light Music (1975) was shown in a 16mm single screen format (1976). This version is a digital translation. The “score” is divided into five movements which are characterised by their differing duration, pitch and accent of sounds. (Lis Rhodes)

Light Reading (1978) by Lis Rhodes

She will act. But how? Act against what? The bloodstained bed suggests a crime… could it be his blood? Could it be her blood? The voice searches for clues… The clues suggest it is language that has trapped her, meanings that have excluded her and a past constructed to control her. Light Reading ends with no single solution. But there is a beginning. Of that she is positive. She will not be looked at but listened to…’ (Felicity Sparrow: Her Image Fades as Her Voice Rises)

Just like Gertrude Stein and Marguerite Duras, great modernist writers of the 20th century, [Lis] Rhodes believes in the inevitable circularity of language, in rhyming and repetition. María Palacios Cruz: “On Reading Lis Rhodes: Writing for the Eye and Ear.” Published in Lis Rhodes: Telling Invents Told.)

At the present time we need to show in a polemical but positive way the destructive and creative aspects of working as women in film, and examine these phenomena as products of our society and the particular society of film/art. Women filmmakers may or may not have made “formalist” films, but is the term itself valid as a means of reconstructing history? Is there a commonly accepted and understood approach? […]Women have already realised the need to research and write their own histories; to describe themselves rather than accept descriptions, images and fragments of “historical evidence” of themselves; and to reject a history that perpetuates a mythological female occasionally glimpsed but never heard. Women are researching and conserving their own histories, creating their own sources of information. Perhaps we can change, are changing, must change the histor[…] (Lis Rhodes: “Whose History?” [1979]. Reprinted in Telling Invents Told)