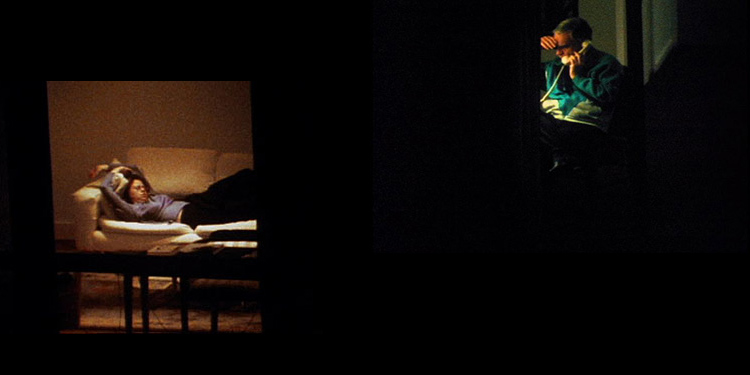

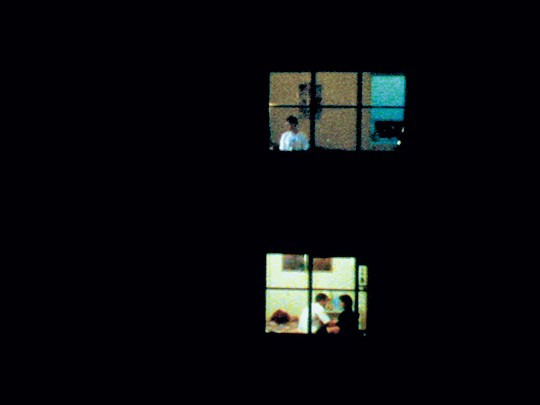

The Sleepers (1999) by Amie Siegel

Sunday, December 8, 2024, 7:30 pm

The Lonely City

Films by Peter Hutton and Amie Siegel

Presented in association with CounterPulse

Admission: $15 General / $12 Cinematheque Members

Event tickets here

Download Program Note

Imagine standing by a window at night, on the sixth or seventeenth or forty-third floor of a building. The city reveals itself as a set of cells, a hundred thousand windows, some darkened and some flooded with green or white or golden light. Inside, strangers swim to and fro, attending to the business of their private hours. You can see them but you can’t reach them, and so this commonplace urban phenomenon, available in any city of the world on any night, conveys to even the most social a tremor of loneliness, its uneasy combination of separation and exposure. (Olivia Laing: The Lonely City)

As we descend into yet another winter, Cinematheque celebrates the approach of the dark season with a revival of two 16mm works considering the subjective experience of urban space through observation and solitary introspection. Amie Siegel’s provocatively voyeuristic The Sleepers (1999)—a film of microdramas within windows, filmed in Chicago—and Peter Hutton’s Budapest Portrait (Memories of a City) (1986) a masterful black and white wander through that stately and silent city.

SCREENING:

Budapest Portrait (Memories of a City) (1986) by Peter Hutton; 16mm, b&w, silent, 30 minutes. Print from Canyon Cinema

The Sleepers (1999) by Amie Siegel; 16mm, color, sound, 45 minutes. Print from the maker

Budapest Portrait (Memories of a City) (1986) by Peter Hutton

“Hutton is a flâneur, a walker in the city. Whereas his contemporary Ernie Gehr typically portrays the street as the site of past and present energies, and other filmmakers focus on the human fauna of the urban scene, Hutton evokes the solitary epiphanies of the metropolitan explorer. […] Budapest Portrait may be his strongest essay yet on the naturalization of the urban landscape. For Hutton, the city is less a social matrix than a verdant asphalt jungle. Close-up portraits of two ancient rag-pickers and a succession of elderly peasant women aside, virtually every other person shown is dominated by the surroundings. Human presence is often suggested merely by indexical signs—photographs, shadows or bullet holes. This relative absence of the figure, together with the harsh chiaroscuro of the winter light, induces a poignant sense of loneliness and isolation. Voluptuously gray, worn and lived in, the city is like a stage set for an invisible drama.” (J. Hoberman: “Peter Hutton: A Tale of Two Cities. Artforum)

The Sleepers (1999) by Amie Siegel

“Shot entirely at night in Siegel’s native Chicago, The Sleepers captures fleeting and obscure moments in the lives of strangers, glimpsed at a distance through the windows of neighboring apartment buildings. While watching the mysterious activity of the anonymous urbanites, a free-association Rear Window is released in the mind of the viewer who has been trained by the cinema to search for intrigue at the furthest edges of the frame.” (Harvard Film Archive)

“[…] The Sleepers is perhaps more connected to [Alfred Hitchcock’s] Vertigo (1958), in which Jimmy Stewart’s character—and the film’s audience—quietly observes Kim Novak for the first third of the movie without understanding what she’s doing; but both Hitchcock films link cinema to the interpretive impulse of imagination. Growing up, I was fascinated by voyeurism. Whether at home, in a ’70s-designed house with large internal windows […] or visiting friends’ high-rise apartments and looking into other buildings, I was already aware of the combination of proximity and distance that connects the watcher and the watched. The Sleepers starts out in a seemingly distanced observational mode, accumulating views of apartments across the way. Its montage is both sequential and simultaneous: shots of individual apartments, seen one after the other, are mixed with wider shots of two or more apartments at a time. But gradually clues emerge to contradict the film’s seeming objectivity…. (Amie Siegel interviewed by Steel Stillman, Art in America)