My Name is Oona (1969) by Gunvor Nelson

Thursday, March 13, 2025, 7:30 pm

Trace Elements

Remembering Gunvor Nelson

Presented in association with Canyon Cinema

Admission: $15 General / $12 Cinematheque Members & Canyon Cinema Members

Event tickets here

Download Program Note

For Nelson, film is a plastic medium whose potential for personal expression demands a denial of conventional film language and syntax on the part of both the maker and the viewer. Her frequently ambiguous and haunting images arise from deeply intuitive personal responses to a subject or to a powerful feeling, and they often bear multilayered metaphorical and tactile meaning. Her complex and exacting montage strategies raise more questions than they answer, and often leave the viewer puzzled once outside of the film’s powerful aesthetic grip. […] [F]rom her first film Schmeerguntz (1966, co-made with Dorothy Wiley), […] Nelson has managed to transform her passion for the feel of pigments applied on flat surfaces to the paradoxically nonphysical interplay of shadow and light. Her films are sensual immersions into sound and image, where every flicker contributes, through its rhythm and texture, to the content of the composition. (Steve Anker: “The Films of Gunvor Nelson.” Published 2002 in Gunvor Nelson: Still Moving, John Sundholm, ed.)

Born 1931 in Kristinehamn, Sweden, artist Gunvor Nelson lived in northern California 1953–1993, during which time she pursued a painting and art-making practice and, in 1966, began filmmaking. In meticulous work created over the subsequent five decades, Nelson’s body of 16mm film (and later digital video) explores interiority and natural landscapes (in the Bay Area as well as in Sweden), presenting a lushly subjective worldview unequaled in the history of the medium. Following her January 2025 passing (at age 93), Cinematheque and Canyon Cinema celebrate the life of this master artist. (Steve Polta)

SCREENING:

Tree–Line (1998) by Gunvor Nelson; digital video, color, sound, 8 minutes. Exhibition file from Filmform

Schmeerguntz (1966) by Gunvor Nelson and Dorothy Wiley; 16mm, color, sound, 15 minutes. Print from Canyon Cinema

My Name is Oona (1969) by Gunvor Nelson; 16mm, color, sound, 10 minutes. Print from Canyon Cinema

Time Being (1991) by Gunvor Nelson; 16mm, color, silent, 8 minutes. Print from Canyon Cinema

Moons Pool (1973) by Gunvor Nelson; 16mm screened as digital video, color, sound, 15 minutes. Exhibition file from Filmform

Light Years (1987) by Gunvor Nelson; 16mm, color, 28 minutes. Print from Canyon Cinema

TRT: 84 minutes

Tree–Line (1998) by Gunvor Nelson

Tree–Line is Nelson’s first video. It is based on sound and image material that accompanied Premiere’s software at the time. Nelson simply began to play with the programme when learning how to work digitally. The starting point of the video is the soundscape and afterwards movement and the image of a tree appears. Tree–Line is a profound reflection on the intersection of film and video, photographic (indexical) media vs. electronic media. (Film Form)

Schmeerguntz (1966) by Gunvor Nelson and Dorothy Wiley

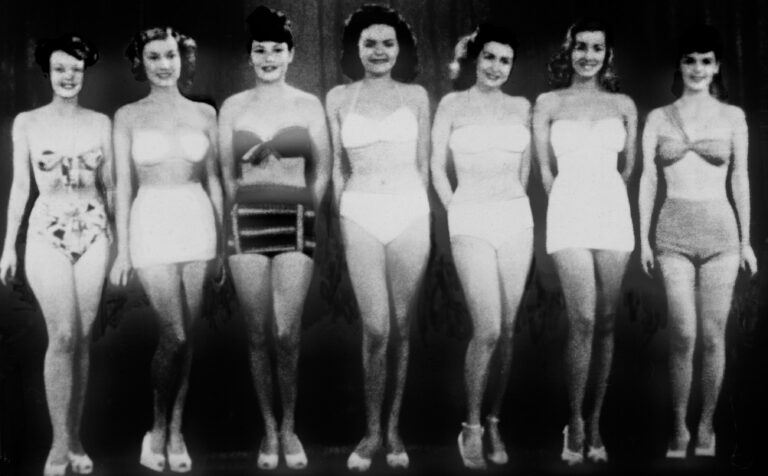

Adopting a decidedly crude and vulgar aesthetic (which happily coincided with the fact that each was working in film for the first time), Nelson and Wiley created a rapid-fire attack on the most cherished of all American icons, motherhood and the home. Images of beauty-pageant contestants and idealized advertising models were jarringly rephotographed from the television screen and rudely intercut with such graphic images as a pregnant woman (Wiley) laboring to get into her underwear, an extreme close-up of excrement being wiped from a baby’s rear end, a woman vomiting […], a filthy toilet being cleaned, a used sanitary napkin dropping from between a pair of legs, and an unrelenting stream of other equally visceral images. Nelson and Wiley profess not to have been influenced by popular feminist theory of the time, but their debunking of one of America’s most potent and carefully controlled myths resonated with audiences throughout the country. (Steve Anker: The Films of Gunvor Nelson)

My Name is Oona (1969) by Gunvor Nelson

My Name ls Oona exists on the opposite end of the artistic spectrum from Kirsa Nicholina (1969). While still focusing on a female subject, here of her young daughter, Nelson chose to create a totally compressed and lyrical evocation of her child’s inner and outer worlds. […] With a soundtrack influenced by Steve Reich, My Name ls Oona correspondingly loops and superimposes black-and-white envisionings of her daughter at play and in contemplation. […] Nelson has said that she knew that she did not want a normal, “cute” picture of Oona: “l think the world she was in and my childhood world are combined there. As a child, you’re pretty secure in your known world, but the rest is very mysterious and scary; maybe there are monsters and trolls lurking out there. even if you’ve never seen them.” (Steve Anker: The Films of Gunvor Nelson)

Time Being (1991) by Gunvor Nelson

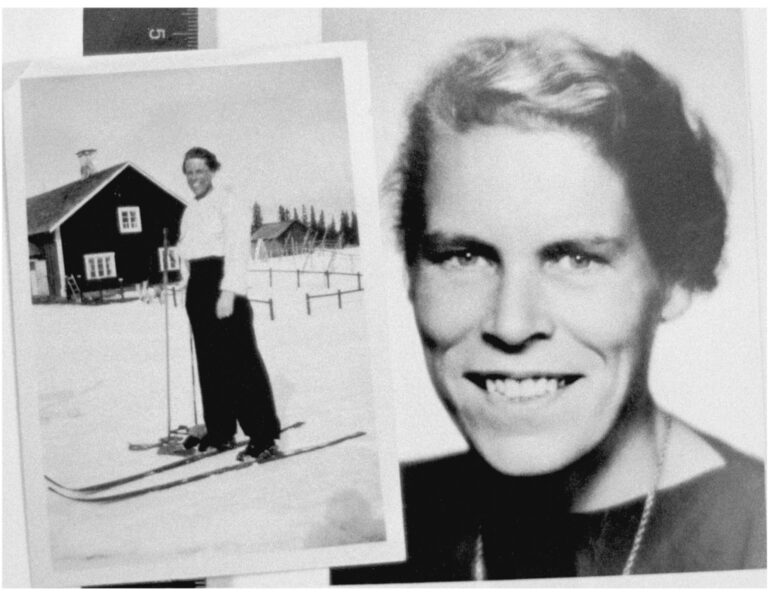

With the simple eloquence reminiscent of a haiku, [Nelson] limits herself to a few lengthy shots of her nearly comatose mother lying in a hospital bed shortly before her death. We can recognize the features of the woman from Trollstenen (1976) and Red Shift (1984), but in this case she is oblivious to the camera and to anyone else, including the filmmaker. Having determined to make one more portrait of her mother, Nelson realized that a direct and uncompromising portrayal of her at that time was all that she could or should convey. After beginning with brief glimpses of photos from her mother’s youth, Nelson cuts to […] an extreme close-up of the old woman’s profile that lasts well over a minute, her mouth open, her eyelid occasionally moving as the only indication of her sentience. Nelson’s unyielding eye once again forces us to see the image of a woman unlike any we are ever permitted to see, and this cinematic gaze intrudes in a way that no natural view could ever equal. (Steve Anker: The Films of Gunvor Nelson)

Moons Pool (1973) by Gunvor Nelson

With Moons Pool, Nelson, by thrusting herself into the picture as the protagonist, created her most personal exploration of the crossover between the physical dimensions of cinema and its unique ability to depict the female body. Focusing on themes of water and the night sky, Moons Pool connects with an elemental sensuality that has long been associated with female unconsciousness. Once again the sound track consists of a stream of spoken words, here an ongoing series of questions and statements made by Nelson herself: “I don’t know why we’re given these bodies to care for, anyway”, “l saw in the sky the moon shining on my face,” and “I see you see me through my body.” Moons Pool is both a celebration and a radical reexperiencing of her bodily limits, while it is at the same time her first filmic self-portrait. (Steve Anker: The Films of Gunvor Nelson)

Image Courtesy of Filmform

Light Years (1987) by Gunvor Nelson

Nelson made seven more films between 1985 and her return to Sweden in 1993. Each in its own way is a composition of exquisitely rendered and rigorously distilled moments that further expands on her previous work. Light Years treats the Swedish rural landscape as an onrushing series of moving vistas beyond reach, but which can still be savored for its formal splendor. In it Nelson hauntingly exposes the fragility of life through the unlikely examples of a vividly rotting apple and the crushing of a tiny fruit worm, as well as deepening her uses of on-screen image manipulation by emotively marking up photographs (again, without her hands ever being evident) of landscapes that we otherwise see as moving pictures. (Steve Anker: The Films of Gunvor Nelson)

Gunvor Nelson (née Grundel: b. July 28, 1931; d. January 6, 2025) grew up in Kristinehamn, Sweden. Her mother was a teacher and her father was the owner and editor-in-chief of the local newspaper, Kristinehamns-Posten. On leaving school she studied at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, but moved to the US and California in 1953 to study art and art history. Nelson met her husband-to-be Robert Nelson when she was studying at the California School of Fine Arts (later known as the San Francisco Art Institute; SFAI). The Nelsons were a vital part of the new film culture that evolved in the San Francisco Bay Area and played a key role in the establishment of Canyon Cinema. Nelson subsequently taught filmmaking at SFAI 1970–1992, moving back to Kristinehamn in 1993. On her return Nelson quickly began working in digital video and was rediscovered in Swedish art circles, resulting in a number of awards and retrospectives both at home and abroad.

Gunvor Nelson (née Grundel: b. July 28, 1931; d. January 6, 2025) grew up in Kristinehamn, Sweden. Her mother was a teacher and her father was the owner and editor-in-chief of the local newspaper, Kristinehamns-Posten. On leaving school she studied at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, but moved to the US and California in 1953 to study art and art history. Nelson met her husband-to-be Robert Nelson when she was studying at the California School of Fine Arts (later known as the San Francisco Art Institute; SFAI). The Nelsons were a vital part of the new film culture that evolved in the San Francisco Bay Area and played a key role in the establishment of Canyon Cinema. Nelson subsequently taught filmmaking at SFAI 1970–1992, moving back to Kristinehamn in 1993. On her return Nelson quickly began working in digital video and was rediscovered in Swedish art circles, resulting in a number of awards and retrospectives both at home and abroad.