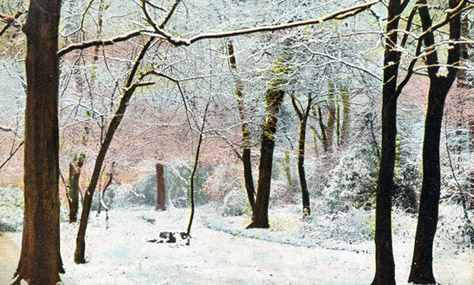

In the Nature of Things (2011) by Barbara Sternberg

Thursday, February 13, 2025, 7:30 pm

Your Life is Like a Candle Burning

Two Films by Barbara Sternberg

Presented in association with The Lab

Admission: $15 General / $12 Cinematheque Members

Event tickets here

Download Program Note

I use many different images and allow for their multiple reading. A sense of something, of the fullness, the complexity and relatedness of the world accumulates over the duration of the film. In depicting the contradictions and paradoxes of life, my films say “and” rather than “or”—light and shadow, good and evil, life and death. I work with images between abstraction and representation; between thinking and feeling. When images are emptied of meaning, they approach being. I think of film as analogous to life. The ephemerality of life is echoed in the temporal nature of film, the “stuff” of life in the emulsion, and the energy, life-force in the rhythmic light pulses. Light, Energy, Life.

— Barbara Sternberg

A central figure in Toronto film communities, Barbara Sternberg is known for a large body of 16mm films which explore film’s physicality, manifesting as ecstatically and sensually experiential, while also provoking overlapping and contradictory perceptual modes. From an expansive body of nearly forty films, this evening’s program presents two long-form works by Sternberg—Like a Dream that Vanishes (1999) and In the Nature of Things (2011)—two far-reaching and ambitious films which dive deep into realms of philosophical speculation, contemporary myth and miracle.

Barbara Sternberg is the co-editor of Moments of Perception: Experimental Film in Canada (2021). This publication will be available for perusal and purchase at the screening and can also be ordered here.

SCREENING:

Like a Dream that Vanishes (1999) by Barbara Sternberg; 16mm, color, sound, 39 minutes. Print from the Canadian Filmmakers’ Distribution Centre

In the Nature of Things (2011) by Barbara Sternberg; 16mm, color, sound, 43 minutes. Print from the Canadian Filmmakers’ Distribution Centre

TRT: 82 minutes

Like a Dream that Vanishes

“The title is from a Jewish prayer which likens our lives to grass that withers, or dust, or fleeting shadows, a whole string of ephemeral things, and the last one is “as a dream that vanishes.” The kind of shooting I do expresses the ephemeral nature of events. We get a little bit and then it’s gone. I wanted to make a film entirely out of leader. There would be bits of colour, with maybe a frame of an image, just these little splashes of colour at the end of a roll. But of course it didn’t end up that way. I think I keep making films because I’ve yet to make the one I see inside.

I wanted to create a visual space that would blur distinctions and boundaries. To move between form and formlessness, creation and dissolution. To conjure this place of dis/appearance, I wanted to use the beginning and ends of camera rolls where the image emerges from or dissolves back into pure light. I think of the emulsion of film as analogous to the “stuff” or sea of life.

While I was working on this film, I met John Davis, a retired philosophy professor. To make overt the philosophical interests that have been below the surface in a lot of my work, I decided to interview him. He begins with Hume and the question of miracles. Is human testimony sufficient to prove the miracle of Christ rising from the dead, for instance? Then he describes the use of language in our attempts at making meaning, which leads him to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theory. This theory accepts that truths can be provable but contradictory, it’s an almost irrational position.

The film alternates between quick snippets of fast camera and blur and coloured leader and sync sound passages of John sitting in a chair. Out of this leader emerges something like a narrative, a chronology. You see a young child, then a four year old running and falling, which might be read as “the fall into the world.” Then people on a ferry (the ark—if you stretch), adolescents on a porch hanging out, jabbing, poking, drinking. Then individuals doing daily things, a woman combing her hair, contemplative, aware of herself. There’s a sax player, a girl alone on a bridge, a guy playing tennis. All of these images are the lived drama of the world. While shooting, I was thinking of Shakespeare’s seven stages of man:

All the world’s a stage

And all the men and women, merely players

that have their exits and their entrances

and one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. At first the infant

Mewling, and puking in the nurse’s arms…

Last scene of all,

that ends this strange eventful history

Is second childishness, and mere oblivion

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

By the end of the film, John’s speaking and the gestural footage draw together. He suggests that philosophy has returned to its roots in wonder and adds, “The world isn’t a very tidy place. We think it is, but it isn’t. It’s a very messy place.” And then he laughs. (Barbara Sternberg interviewed by Mike Hoolboom)

In the Nature of Things

The central image of In the Nature of Things is the Forest—sometimes fearful, sometimes a refuge, always mysterious—and the multiple associations and myths embedded in it—myths within which we live and which live within us—our collective history. But, unexpected moments, intensified fragments, catch us unawares—the present confronts us. For Emmanuel Levinas, the face-to-face encounter with another is a privileged phenomenon in which the person’s proximity and distance are both strongly felt: “The face opens the primordial discourse whose first word is obligation… the face speaks… the first word of the face is ‘Thou shalt not kill;’ it is an order.” In the Nature of Things continues my examination of the oppositions played out dialectically and enmeshed in our experience of living: culture/nature, lived history /recorded, belonging/destroying, communal/individual, innocence/danger, young/old, living/dying. This is an autumnal film—twilight—a film of old age. Just as Forest is a transitional space, so Old Age is a transitional time. (Barbara Sternberg)

Thomas Bernhard’s The Voice Imitator [text which appears throughout the In the Nature of Things] is a darkly comic work. A series of parable-like anecdotes—some drawn from newspaper reports, some from conversation, some from hearsay—this satire is both subtle and acerbic. What initially appear to be quaint little stories inevitably indict the sterility and callousness of modern life, not just in urban centers but everywhere. Bernhard’s text is a central reference in Sternberg’s In the Nature of Things. (Pleasure Dome, Toronto)

Moments of Perception: Experimental Film in Canada

Moments of Perception: Experimental Film in Canada

by Jim Shedden & Barbara Sternberg

order now!